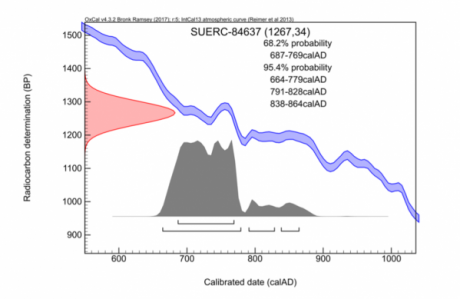

This week, we got our first set of radiocarbon dates back from the lab, and the results couldn’t be more positive. Analysis shows that the material we sent for dating is from AD 660-860!

In short, these results confirm that the heart of Princess Aebbe’s Anglo-Saxon monastery is probably underneath the later medieval Coldingham Priory. Specifically, they prove that the huge mound of animal bone we found dates to the very same time that Princess Aebbe’s monastery was in existence. It’s the final piece of evidence we needed before we could confidently declare that we have indeed found the remains of her monastery!

Princess Aebbe is a great example of an Anglo-Saxon woman who shaped British history. She was instrumental in the early spread of Christianity along the north east coast and, despite some criticism of the unruly conduct at her monastery, contemporary sources suggest that she was an incredibly well-respected figure. Born a pagan princess, she became an abbess, and was later made a saint.

She was also the sister of King Oswald, who is celebrated as the great king who founded the famous monastery on Lindisfarne, which became the first community in Britain to be raided by Vikings, and has since gone on to become one of Britain’s most iconic Anglo-Saxon sites.

Lindisfarne and Coldingham are two halves of the same story, each created by one of two siblings who were on a shared mission to bring Christianity to their homeland, and reclaim their family throne.

While Oswald’s half of the story at Lindisfarne is well known, Aebbe’s half of the story at Coldingham is not. And that’s what makes this discovery so important: now that we’ve pin-pointed her monastery, we can help bring her story back to life!

Hundreds of pieces of animal bone produced the evidence we needed

During the excavation, we recovered hundreds of pieces of butchered animal bone, including cattle, horse pig, sheep/goat, domestic fowl and red deer. The animal bone spreads represent the disposal of carcasses after processing with the high value joints of meat consumed elsewhere within the complex. They were eating well!

We sent a piece of animal tooth off to the lab for radiocarbon dating, and the results came back as between 664 – 864 AD, indicating that the pile of bone is Anglo-Saxon in date. We can now confidently say that substantial activity was taking place right in the centre of Coldingham at the time that Aebbe’s monastery existed.

And it’s all thanks to YOU GUYS!

You might remember that not only did we crowdfund the excavation, and do the dig with hands-on help from our crowdfunders, in the true spirit of collaborative archaeology, we also asked our followers to help us choose where to dig.

We knew it wouldn’t be possible to attempt to dig the whole site, so we drew up a shortlist and asked our you guys to help narrow down the choices. Nearly 700 people pored over maps and descriptions before giving their vote.

And you all made a very smart decision, shunning some of the more glamorous suggestions we put forward in favour of a big, dark splodge on the map. We might not have excavated that particular spot if it hadn’t been their top choice. As it turns out, this is where we found the animal bones that enabled us to get a very secure radiocarbon date!

Piecing the evidence together

There isn’t one single clue that points to this being Aebbe’s monastery, there are many – and together they fit the profile of an Anglo-Saxon monastery. Anglo-Saxon monasteries typically included lots of different wooden buildings spread out within a large area enclosed by a boundary ditch, with traces of small-scale industries, farming, and even large piles of rubbish (like the huge spread of bones we found) around the edges.

Aebbe’s monastery was recorded by the medieval historian Bede as being at a place called ‘Urbs Coludi’, which became ‘Colodaesburg’ in Anglo-Saxon, and later Coldingham, so we knew from the start that it was somewhere in the vicinity.

There is also a very strong history of later Benedictine priories being built on top of earlier Anglo-Saxon ones, including some of the most famous ones like Lindisfarne, and we have Coldingham Priory apparently sat right in the middle of our site!

The large, encircling ditch is also typical of a vallum (monastic boundary). They weren’t necessarily deep, intimidating defensive structures, more like a symbolic marker to show that you were crossing onto entering holy ground. It’s also the scale of the boundary ditch, and the area that it encompasses, which gives us an indication of the scale of the compound – it would be very unusual for it to be anything else at that size.

The huge pile of butchered animal bone, which included deer and cattle, also points to a large community who were living and eating together. As well as being radiocarbon dated, they were analysed by a specialist who concluded that, based on which joints and bones were left, they were eating the ‘best bits’.

There were also several earlier archaeological clues from smaller excavations in the immediate vicinity, including early Christian burials, pieces of an Anglo-Saxon belt fitting, and fragments of sculpture. But it’s only now, after a larger excavation complete with fresh radiocarbon dates, that we can clearly see the bigger picture – including the ditch.

Previous attempts to find Aebbe’s monastery had focused on two clifftop locations on the headland, St Abb’s and Kirk Hill, but neither produced firm evidence consistent with an extensive, and wealthy Anglo-Saxon monastery.

Some of the remains at Kirk Hill could certainly be contemporary, and perhaps even used by people at the monastery, but they didn’t provide enough to suggest that this was the site of the monastery itself, whereas the evidence from the priory site does!

So let’s say it loud, and let’s say it proud… here’s to Aebbe and her monastery!