The artefacts have already told us a lot, but it’s what this map reveals that’s really exciting…

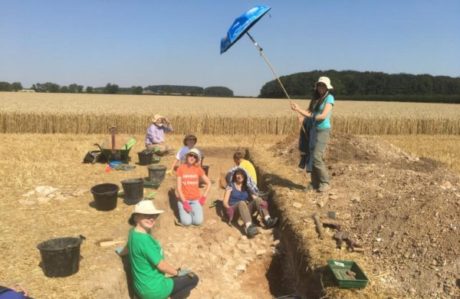

It’s been an incredible year for discoveries at DigVentures. With help from people all over the world, we’ve investigated archaeological sites from Cornwall to Scotland. But for me, the real icing on the cake came slightly closer to home, when we unearthed a Roman settlement in the East Riding of Yorkshire.

Encountering Roman sites is nothing new, but the artefacts we found told us it was one of the earliest ever to be discovered in the region so far. That in itself is pretty exciting, but it’s when we sit back and think the early Roman landscape our site sits in, and use maps to help us tell its story, that things really start to get interesting interesting.

How early is early?

I could write at great length about all the cool things we found, but that’s not for now – you’ll just have to wait for the official report to come out! Or, you can read a little bit more from articles published in The Telegraph, The Guardian, and in our Site Diary.

Pottery from the excavation near Driffield.

What’s important to know is that as a whole, the pottery assemblage is not only pretty rare for East Yorkshire, but most of it was probably made in York around towards the end of the 1st century AD, and the beginning of the 2nd century AD, with some nice imports from France and the Mediterranean.

Coins of Titus (AD 79-81) and Vespasian (AD 69-70)

This matches up perfectly with the coins, many of which date to the rule of Vespasian (AD 69-79) and some from Titus (AD 79-81).

Such early dates are really exciting, especially in East Yorkshire, because the Romans didn’t establish a base at York (Eboracum) until AD 71. Our site near Driffield appears to date to the same period, which means we could well be looking at a site that was occupied by some of the very first Romans north of the Humber.

But that leaves us with two big questions: what exactly were the Romans doing all the way out near Driffield at this time? And how could we possibly find out?

Working hypothesis: it’s a mansio

One theory proposed by our pottery specialist is that we may have stumbled across the site of a mansio, or posting station.

Mansios were effectively stopping places that were maintained by the government for use by officials, and found at regular intervals along roads. Immediately this got my GIS (geographic information systems) senses tingling, so I took to the computer to find out everything I could about early Roman settlement in the surrounding landscape.

Testing the theory

There’s actually quite a lot of information out there online: have a look at The Rural Settlement of Roman Britain, Roman Britain and The Secret History of the Roman Roads of Britain.

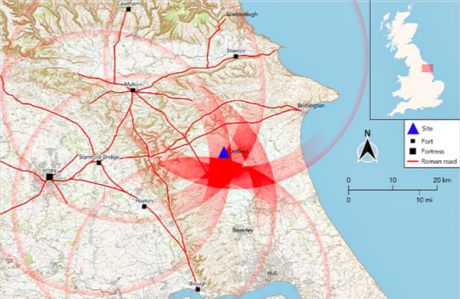

But strip it back to the bare information you need and put them all on a map, and this is what you get:

Map illustrating all known pre-Hadrianic forts in the region (pre AD 117), and all known Roman roads. These roads won’t necessarily all have been built by the 1st century AD, but they do add a bit of perspective to Roman influence in the landscape at the time. 📷 Chris Casswell

Having a clear basemap of your study area is a great place to start before delving any deeper, but where to go from there?

The speed of an ox-drawn cart

To test the theory of whether Driffield might once have been the site of a mansio, we’d need to establish whether it was any useful distance from other key sites in the area, such as those on the basemap. And for that, we’d need some information about the typical distance between a fort and a posting station.

Initially I consulted Wikipedia, which led me on to William Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. It seems that the general consensus is that 30km would have been around the maximum distance an ox-drawn cart could travel in a day.

Each station would have probably been placed around 25-30km apart, to account for variations in local topography and road conditions. Plug this information into a map, and this is what you get:

Map showing 25-30km buffer intersections from Driffield’s five closest Roman forts. When we look at the areas of overlap, we end up with quite a neat and informative graphic showing where we might expect to find a posting station in pre-Hadrianic Roman East Yorkshire… Shout when you see it!

Conclusion: Driffield is a prime location for a posting station!

The map shows a clear hotspot around Driffield, making it a prime location for a posting station. In short, it’s a great piece of evidence that supports our theory!

Unfortunately, that doesn’t mean we can start claiming to have discovered an early Roman mansio… yet.

Before we can say whether the theory really holds up, we still need to establish the chronology of all the different archaeological layers on the site, get specialist reports on all the finds and do some more research into other sites in the region.

Oh, and of course… we’ve still got to return to Driffield to continue the excavation in August 2019, and find out what other evidence we can recover. If you want to help us, just click here.

If this update gets your GIS senses tingling too, you can read the extended version.