Opening trenches is a lengthy process, but the real question on everybody’s lips is ‘how do you know where to put them in the first place?’

It took a full day’s work to open three trenches and get them ready for excavation. First, we needed Andy to come along with his GPS device and locate the corners.

Next we marked out the edges with yellow spray paint. Only then could James start stripping the topsoil with his big yellow JCB.

Then along come the archaeologists to remove the buffer by hand, and to clean back the leftover soil with shovels to straighten the edges, and trowels, mattocks and brushes and gently approach the archaeological horizon.

Once the trenches are spick and span with a few glimpses of archaeology cheekily showing themselves through the surface, they’re finally ready for the process of excavation to start and find out what’s lurking inside them.

But the big question on everybody’s lips is… how did you know where to put the trenches in the first place? The answer is, with a very good set of geophysics results and a bit of archaeological deduction…

To the east of the village, we’ve opened two trenches in the hope that we’ll find some of the buildings that once made up the Anglo-Saxon monastery.

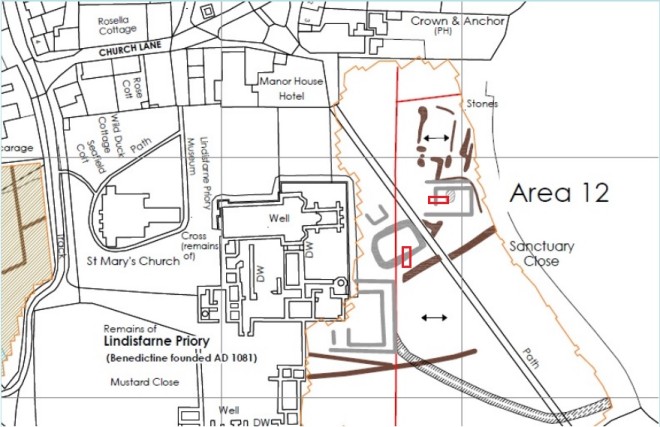

The geophysics results showed a series of linear and rectilinear features just to the east of the high medieval priory.

Interpretation of the geophysics results by Durham University.

The square feature adjoined to the priory looks very much like a previously unknown second cloister, but the others? Well, they’re in an area that’s known to be outside the high medieval priory, and post-medieval maps show no buildings were built in the area after that.

If it’s not post-medieval, and it’s not high medieval, then by a process of elimination, these features can only be early medieval, right? Possibly. And that’s exactly why we’ve put two trenches over these features; to see if we can find any evidence that gives us a firm date.

To the west of the village, we’ve opened one much longer, thinner trench in a field that overlooks St Cuthbert’s Isle.

There are lots of theories about where the perimeter of the Anglo-Saxon monastery lay, but once again, the geophysics results showed up some strong signals; strong enough to suggest that metalworking may have been carried out in the area.

As we mentioned in our previous Site Diary, metalworking and early medieval monastic boundaries seem to go hand in hand.