Not all hillforts were on hills, and that’s what makes Oldbury Camp so very interesting

There are around 3,300 ‘defended enclosures’ in Britain. Having developed in the Late Bronze and Early Iron Age (from approximately 1,000 BC) and remained in used by the ancient Britons until the Roman conquest, they come in all shapes and sizes. Some are ovoid, some are rectilinear, some have single defensive banks and some have many. Some are interpreted as being defensive, some for settlement, some for storing grain and others for showing off. But if there’s one thing they all seem to have in common, it’s that they’re all on hilltops, right?

Wrong. There is in fact a surprising richness of lowland hillforts around the country. It’s just that (to put it simply) compared to their more elevated counterparts they have been archaeologically overlooked, while the proliferation of the name only compounds this presumption. And yet these lowland hillforts have so much to tell us.

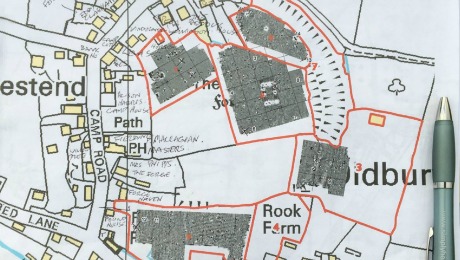

Oldbury Camp is one such example. Known locally as “The Toot”, this ‘hillfort’ occupies a strategic, but low-lying prominence just 200m south of Oldbury Pill (pill is the local name for creek). In archaeology jargon, it is a ‘univallate’ hillfort, made of a single rampart comprising a double bank and ditch.

Today, the outer bank still stands up to 1.5m tall in places, while the inner bank reaches a whopping 1.9m. Both survive on the north and east sides, with only a single bank remaining to the west. Meanwhile the southern half of the site is fronted by a huge earthwork platform about 150m x 75m in size. It’s possible that this platform was once some sort of wharf, although it might also be the result of later agricultural activity levelling the rampart in this area.

The Cotswolds are famous for a major group of hillforts, but Oldbury Camp is one of several that are peripheral to this group and do not fit the traditional mould. And that’s what makes it so important; Oldbury Camp’s lowland setting, well-preserved ramparts and unusual character all mean it’s (literally) in a position to help us understand the phenomenon of defended enclosures in completely new ways.

Around the country, there are a number of low-lying parallels, especially in eastern England, and in other lowland and wetland locations. Some of these have been dubbed ‘marsh forts’, owing to the strategic positions they seem to occupy in controlling access to and from rivers, creeks and wetlands. However, compared to their more dramatic hilltop counterparts, research is only really just beginning.

Hillforts come in all shapes and sizes and, as it turns out, not all of them were built on hills. It is only by investigating sites like Oldbury Camp, and their more varied locations, that we will truly begin to understand the phenomenon of these monumental Iron Age enclosures.