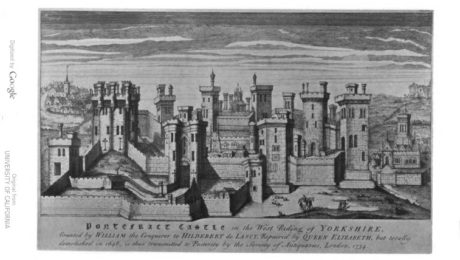

Pontefract Castle was one of England’s most impressive and strongest fortresses throughout the medieval period and beyond.

If what’s left of the walls of the castle could talk, they would tell stories of fearsome battles and long, lonely sieges, of starvation and destruction, of royal scandal and even the production of liquorice…

The hill on which Pontefract Castle now sits was once home to an Anglo-Saxon burial ground and Anglo-Saxon manor, with the first historical record of a castle on the site appearing around 1070, shortly after the Norman Conquest. The castle was built by Ilbert de Lacy, who had fought with William the Conqueror at the battle of Hastings and had been given the Honour of Pontefract as a reward for his valour in battle. De Lacy’s original fortress would have been made of wood, and built to inspire fear in the native Anglo-Saxon population, who were not enamoured with their new Norman rulers. Over the course of several centuries, the wooden fortress was replaced with stone.

By the 13th century, Pontefract Castle had been transformed from a humble wooden fort to a formidable stronghold. In fact, the castle was so impressive that when Oliver Cromwell attacked in 1649, he called it ‘one of the strongest inland garrisons in the kingdom’. Its robust defences and position on a rocky outcrop made it almost impenetrable, while the strategic inland location meant the castle played a crucial role in politics and the balance of power in the North of England.

There are even more reasons why Pontefract Castle is unusual and very special. The keep has a rare Quatrefoil design, which puts it among good company with other examples including Clifford’s Tower, York and at the Château d’Étampes in France. Pontefract also has a torre albarrana, known as Skillington Tower, a fortification almost unknown outside the Iberian Peninsular; a torre albarrana is a type of defensive tower connected to a curtain wall by a bridge or an arcade. Its purpose was to increase the defender’s range of flanking fire.

The Key to the North

Today, the castle is surrounded by the modern town of Pontefract, but in its heyday it commanded two of England’s busiest and most important highways: the north road, and the route west over the River Aire and the Pennines, earning it the nickname of ‘The Key to the North’.

A deposed Richard II is believed to have been imprisoned and died in the castle in 1400; mentioned in William Shakespeare’s play Richard III, ‘Pomfret, Pomfret! O thou bloody prison’.

In fact, the dungeons were notorious in medieval England; hollowed out of the bedrock 35 feet below the castle, it was quite common for prisoners to be left in the pitch black depths for weeks at a time. Many scratched their names into the cold, damp walls, and some of these names can still be seen today.

A castle destroyed by its own people

During the English Civil War, which broke out in 1642, the castle was a strategic Royalist stronghold and the site of the longest siege of any place during the civil war.

When the war finally ended and the castle was handed over to the Parliamentarians, Oliver Cromwell was enthusiastic about ensuring its destruction. He turned to the townspeople of Pontefract and encouraged them to petition Parliament to sanction the demolition of the castle. Tired of armies pillaging the town en route to the fortress, the townspeople of Pontefract were eager to help him. On 27 March 1649, Parliament gave orders that Pontefract Castle should be ‘totally demolished & levelled to the ground’ and for materials from the castle to be sold off.

The castle was dismantled in several stages, leaving little of its once mighty outer walls, although a few parts of the curtain wall and inner walls have survived. Thankfully, the story is a little different below ground, where the 11th century cellars (which were used for storing military equipment) remain largely intact. Traces of the inner bailey gatehouse have also been found, which have now become the subject of an archaeological investigation.

Lovely liquorice

The castle soon took on a new life, and became an emblem of the town. From around 1614, the town produced small liquorice sweets known as Pontefract Cakes, or Yorkshire Pennies, often stamped with a picture of the castle.

As liquorice grew in popularity during the Victorian period in the 19th century, the land surrounding the castle ruins was used to grow the crop. The Victorians even excavated some of the many dungeons in order to store it. Later, it became cheaper to import liquorice from Spain, which is why liquorice is locally known as ‘Spanish’.

Today, liquorice still has a big influence on the town, and Pontefract now hosts an annual Liquorice Festival, and the castle is iconic of the region’s history.