Cave archaeologists have their own unique set of jargon words. Our hand-picked selection is so good that even if it doesn’t set you on the path to enlightenment, it will at the very least help you win at Scrabble.

For some people, caves are a geological wonderland for recreational use; and for others, they’re a treasure trove of sensitive archaeological evidence dating all the way back to the Ice Age and beyond.

The problem is that cave researchers often choose to talk about this exciting, adventurous and fascinating subject using words so scholarly and bewildering they’ll leave you thumbing through a bedside dictionary.

In this jargon buster blog we’ve picked out some of the most delightful words you’re likely to hear coming out of a cave archaeologist’s mouth. If it doesn’t set you on your way to enlightenment and understanding, it will at the very least help you win at Scrabble.

But before you dig in, let’s not forget the most important thing of all… We’re crowdfunding an excavation to find out what’s inside Ben Scar Cave. It’s as much designed for cave-enthusiasts to learn about archaeology (and vice versa) as it is for people who have never tried either of these things but would be up for giving both a go. Fancy it? Make a pledge (however big or small) and you get to come and dig with us for a day!

Ma

Let’s start with something that gives a sense of the vast expanses of time that cave archaeologists regularly deal with. Many of Yorkshire’s caves formed millions of years ago, and can contain archaeological or environmental evidence stretching back hundreds of thousands of years. While normal archaeologists fuss over decades and centuries with things like BC and AD, cave archaeologists use ‘Ma’ as shorthand for millions to save themselves a precious few seconds whenever they note the date of something.

Karst

Karsts are landscapes formed when acidic water breaks down soluble bedrock like limestone, leading to the formation of extensive cave systems just like (yup, you’ve guessed it) the Yorkshire Dales.

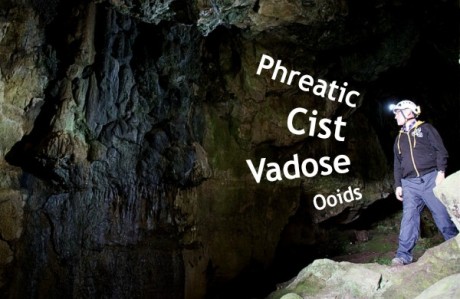

Phreatic

Caves and underground passages develop when water wears away rock, but this happens in a number of different ways. A phreatic cave is one that develops under the water table. The water exerts pressure on all sides, producing passages that are roughly circular in profile.

Vadose

Unlike phreatic caves, vadose caves develop above the water table, with the water eating downwards into the floor of the cave, leaving distinctive keyhole-shaped passages for us to explore.

Relict

When there’s no longer any water passing through, caves and passages are termed relict. Now, they start filling up, often through speleothem accretion.

Accretion

You could say ‘grow,’ ‘accumulate,’ or ‘fill up’, but cave archaeologists generally prefer to say accretion because it implies very small increments building up over long timescales.

Speleothem

Speleothem is a catchall term for the rock structures that grow in caves over millennia from the tiny calcite deposits left each time a drop of water falls. The most famous of these are stalactites, which grow downwards from the ceiling, and stalagmites, which grow upwards from the floor. They can be examined for dating and environmental evidence. Bonus points if you already knew which is which…

Cist

Not to be confused with karst, cist is prounounced ‘kissed’ not ‘sissed’ (that’s an error that would give your bluff-game away), and describes a burial where the body has been placed in a stone-lined grave, or coffin-like box made of stone-slabs. Generally found in cairns and barrows, they’ve also been found in caves. Raven Scar Cave, for example, held the remains of more than 20 late Neolithic burials, of which many were associated with three slab-and-boulder built stone cists. This is where archaeologists also famously found a bone whistle (only two have been found in the country).

Ooids

Oolite or ‘egg stone’ is a sedimentary rock formed from ooids (spherical grains of concentric layers) and looks like it is made of lots tiny little eggs, kind of like a geology’s own version of polystyrene.

Talus

To most archaeologists, talus will mean ankle bone, but to a cave archaeologist it means a pile of rock debris that has gathered at the bottom of a rockface or cave entrance.

Loess

Loess is a very fine glacial sediment consisting of silt deposited in the landscape by the winds that blow off the glaciers and often then transported into cave systems by water.

Cavemilk

Also known as moonmilk, this creamy, white, magical-looking soft calcite deposit is often found inside limestone caves, and reputedly has antibiotic properties.

Guano

Where would we be without mentioning guano? Generally speaking, it refers to bird poo, but if you hear it from a cave archaeologist, you can bet your bottom dollar they’re talking bat poo – and probably complaining that it’s mucking up their phosphate readings too).

Pitfall

‘Bone caves’ is a catchall term for caves filled with ancient animal bones, and which have provided an astonishing amount of environmental data including proof that there were multiple Ice Ages, and that elephants once lived in the Yorkshire Dales. They fit into three rough categories: occupied, den, and pitfall – an open shaft into which animals fall. Over millennia, bones accumulate, get covered by sediments, and the cycle repeats. Cupcake Cave, excavated by local cavers in Leck Fell, is an excellent example.

Coprolite

While we’re on the subject of poo, coprolites are fossilised ones. If you’re the kind of person who would get excited by discovering 120,000 year old hyena coprolite in the Yorkshire Dales, then this dig is for you.

Megaloceros giganteus

Not a dinosaur, Megaloceros giganteus is actually an extinct species of giant deer that once grazed the Yorkshire Dales 120,000 years ago, bits of which are often found in caves and whose antlers could span over 3m from tip to tip. Yes, really.

Magdalenian

Magdalenian describes one of the later cultures of the Upper Palaeolithic (the last bit of the Old Stone Age) found across western Europe, lasting from around 17,000 to 12,000 years ago, and named for the ‘type site’ at La Madeleine, a rock shelter in Dordogne, France. These hunter-gatherers had an array of artistically carved weapons and evidence of their presence, including spearpoints and butchered horse bones, has been found in Victoria Cave, Yorkshire.

Creswellian

Creswellian is pretty much the same as Late Magdalenian (or Upper Palaelithic), but specifically within Britain. Coined by Dorothy Garrod after remains were discovered at Creswell Crags in Derbyshire, they date to the period between 15,000 and 13,800 years ago, just before the last Ice Age started and large swathes of Britain were left uninhabited.

Knap

No, it’s not time to take a break from all these delightful words, it’s time to talk about the fine art of crafting stone tools from rock through a process known as knapping. Chances are that if you join us, you’ll get to see one of our team giving it a go.

Lithic

On any prehistoric site, you’ll encounter heaps of stone tool terminology, like flake, blade, core, scraper, and burin. After a day in the trenches, you’ll be using them fluently in no time. Lithic just means stone. Once you realise this, and that ‘palaeo’ means old, and ‘neo’ means new, suddenly all those terms like Palaeolithic (old stone age) and Neolithic (new stone age) suddenly start to make a whole lot more sense.

Hearth

To a cave archaeologist, a small patch of ashen ground is great cause for excitement, because it generally represents the remains of a fireplace or hearth, a great indication that the cave has been used by humans. Hard to spot until you’ve seen one, the remains of hearths and evidence of burning is well preserved in many locations.

Votive

As well as bones, tools and other ‘Stone Age’ items, Yorkshire’s caves contain more recent (relatively speaking) artefacts too. Take, for example, the curious pierced bone spoons and beautiful Romano-British brooches found at Victoria Cave. You don’t just drop these things in the deepest, darkest depths of a cave by accident do you? They must have been put there on purpose, in which case you’ll probably describe them as ritual, sacred or even… votive.