Meet Ben Scar: the cave that *could* become Yorkshire’s next archaeological superstar… with your help!

The Yorkshire Dales is famous for many things, from its distinctive limestone uplands right down to its seemingly endless network of subterranean caves, which have produced rare archaeological remains dating all the way back to the Ice Age.

Caves can be treasure troves, with vital information trapped in their sediments, as well as scattered on the ground. Each tiny fragment recovered has the potential to add a new chapter to the story of prehistoric Britain. The Yorkshire Dales counts in its midst such geological celebrities as Attermire, Victoria, Jubilee and Kinsey caves, in which archaeologists have uncovered evidence of dramatic climate change, Magdalenian hunter-gatherers, and even of Romano-British cave cults who later used these spaces for burials and possibly worship.

New caves are being opened all the time and for archaeologists, each one is a potential mine of information. But to retrieve it, cave archaeologists rely on people entering these caves for the first time to keep an eye out for potential archaeological remains.

Ben Scar Cave is one that remains (to our knowledge) archaeologically uninvestigated, and yet it’s in prime cave archaeology territory. We’re crowdfunding an excavation that’s uniting cavers, archaeologists and the public in order to find out what’s inside, and better understand the discoveries made by archaeologists in the 19th and 20th centuries. Pledge your support and you can join us for a day and learn hands-on about cave archaeology all while helping to investigate Yorkshire’s ancient past.

Why Ben Scar Cave?

Ben Scar is ituated in the Yorkshire Dales National Park, in the limestone uplands above Settle, in an area first made famous in archaeological circles by Joseph Jackson and the Settle Cave Exploration Committee in the 1870s. The archaeological potential is all about location, location, location…

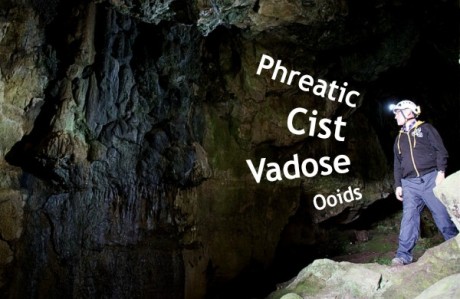

The cave entrance is at an altitude of 451m, and is developed in gently dipping beds of Lower Carboniferous Asbian Age Limestones. For all you geologists out there, the landscape in front of the entrance breaks into the mid-Craven fault scarp, which defines the southern edge of the Askrigg Block.

The entrance itself is 4.5 m wide, with an impressive overhang approximately 7m high that affords good shelter. The remains of an enclosure surround the entrance, and a low crawl leads to two small chambers.

A south facing entrance in Settle Bank looks down to an area of mire, which for thousands of years held water, but was drained at the beginning of the 20th century.

Further afield we can see across the Lower Ribble valley to the sloping heights of Pendle Hill, famed for its coven of ‘witches’ who reputedly practiced their black arts under the shadow of the dark shrouded fell.

The neighbouring caves

Ben Scar’s neighbouring caves have provided a legacy of animal bones stretching from the Pleistocene through to the current Holocene. They’ve provided evidence that hyena, elephant, lion and rhino once roamed the Yorkshire Dales 125,000 years ago, and that brown bears hibernated in many of these caves 14,000 years ago.

Archaeological evidence for human use of the caves within the area is just as amazing, from Neolithic tools and burials in Jubilee Cave, to Romano-British ‘cave cult’ deposits in Victoria and Attermire cave, where the remains of a chariot were recovered in the 1930s on a ledge so narrow it is uncomfortable to walk along.

Two Romano-British camps hve been found in the surrounding fells, one of which has potential evidence of metal-working. The second camp lies below Ben Scar Cave and is still surrounded in a certain veil of mystery. Mine shafts containing azurite, malachite and barytes lie within the immediate area, and below the cave is an ancient monastic trackway linking Malham to Settle.

So what do we think might be inside Ben Scar Cave?

Finding a few more Pleistocene animal bones would be awesome, while more evidence of Romano-British remains could help prove theories about the emergence of a ‘cave cult’ in the area.

But this kind of evidence is more than just awesome, or surprising. It carries rare scientific evidence that could significantly increase our palaeoenvironmental knowledge of the area.

On top of that, there is an enclosure surrounding the cave entrance, which could give us even more insight into human use of the cave, and whether it had anything to do with stock management.

More dating evidence could contextualise the cave with the surrounding landscape including Victoria Cave, Victoria Camp, Attermire Cave, Horseshoe Cave and Attermire Camp. But, the only way to find out for sure is for YOU to come and help us dig.