Throughout history, people have sought out dark places, for burials, worship, solace and even play. A fascinating new book edited by Marion Dowd sets out to explore the archaeology of darkness, from the Palaeolithic to the present day.

These days, our cities are never dark, are homes are always lit and we rarely experience real darkness. Even sitting in the cinema, our faces are lit up by the filmscreen, or even (heaven forbid!) the pale blue glow of a smartphone.

But archaeology shows us that throughout history, people have sought out dark places, for burials, for votive deposition and sometimes for retreat or religious ritual away from the wider community.

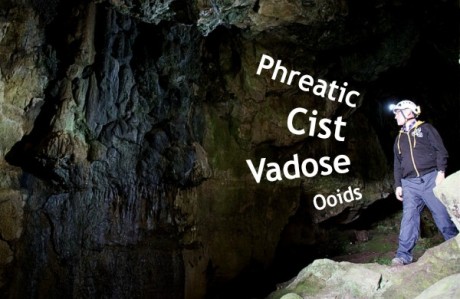

As an archaeologist and caver, I’m one of the few that makes a habit of exploring places with no natural light, which is why I got so excited about a new book that’s just been published.

‘The Archaeology of Darkness’, edited by Marion Dowd sets out to examine the role of darkness in the human condition, from the Palaeolithic use of deep caves, through to the mortuary practices of the Neolithic, of Bronze Age miners excavating passages thousands of years ago, right up to the experiences of archaeologists exploring caves today, and covers everything from the role of darkness in religion, ritual, work and even play.

All of which brings me to my own experience of the archaeology of darkness. What is it like to dig in such dark places? And to discover things that people left there tens or even hundreds of generations ago?

I’ve been exploring the archaeological secrets hidden deep inside the caves of the Yorkshire Dales National Park. Some were used for burials, while others seem to have been used by a Romano-British cave cult, who left small votive offerings in their darkest recesses.

Neolithic cave burials have been documented in the region since E Jones excavated at Elbolton Cave in 1888. Other caves which held buried Neoliths include Sewells cave on Giggleswick scar, excavated by the Tot Lord (he excavated Jubilee too) and Raven Scar Cave in Chapel le Dale, where the archaeologists recovered 20 burials and a bone whistle (only two have been found in the country) which still whistles a tune. One reason why they may have used caves for burial in the Neolithic was to be a bit like their cousins in the lowlands who used barrows for the burial of their dead.

But what’s really amazing is the story of one particular archaeologist who discovered and excavated one of the area’s star caves in the 1800s, which not only contained the remains of Ice Age hunters, but also trinkets now thought to have been deposited by a Romano-British cave cult.

His name was Joseph Jackson, and he was just 20 years old when he found a chamber deep inside Victoria Cave. It was pitch black, and sealed from all natural light, but it was full of archaeological remains. Originally a plumber and glazier, Joseph had no formal training in archaeology, but every evening after work, he would come up and spend the night excavating the pitch-black chambers by candlelight on his own. By the time he finished, he’d become a professional archaeologist.

Last November, we took an intrepid group of Venturers on a Dirty Weekend to explore some of these caves. The weather that day was generally cold and wet, and we headed to Jubilee Cave to take a look. As we walked inside, it was as though we’d entered a portal. Although the cave was damp, we had moved out of the rain and the wind, and through the darkness the still air of the cave enveloped us all.

A beam of light entered the cave from the entrance, but as we moved around a corner deeper into the cave, the light could reach us no more.

So what was it like to be in this cave four thousand years ago, just like the Neolithic people some of whose remains have been found inside this cave and others like it?

We turned off our ‘modern lighting’ sets and lit the candles, and let the flame throb like a slow pulse and then burst into light – the warm glow of the candle reaching out into the dark corners of the cave.

In this flickering half-light, the sound in the cave seemed to be amplified. The drip of water into pools rang out like a chime, and with the soft light making the shadows dance along the wall of the cave, your senses are so heightened that you become aware of your own heartbeat and perhaps even the blood of your ancestors pulsing away in the darkness.

It really was a back-to-nature experience, and is one that you can come and experience on the next stage of our ‘Under the Uplands’ adventure.